Matobo National Park: Lasting relics of an incredible people

By Megan Gilbert

On either side of the track, Zimbabwe unfolded before us. An endless Africa opened up beneath a bright blue sky. We breezed past, eagerly looking out the train windows on our way to Victoria Falls.

That bright blue sky stretched across a dry Zimbabwe, over baobab trees and pastel-colored villages where excited children waved. Women balanced buckets on their head as they walked from the streams, almost bare now in the dry season, and cattle with downturned horns devoured dry cornstalks.

From the train car windows, we had spotted giraffe in the dry bush north of Pretoria, and hippos from the bridge over the “great grey-green greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever trees,” as Rudyard Kipling said.

After three days on the train, relaxing in luxury, I was excited to stretch my legs beneath the bright midday sun, feel the warm breeze of a Zimbabwe winter, and explore another treasure of the African continent. The train pulled into the station at Bulawayo, and we boarded our private bus to Matobo National Park.

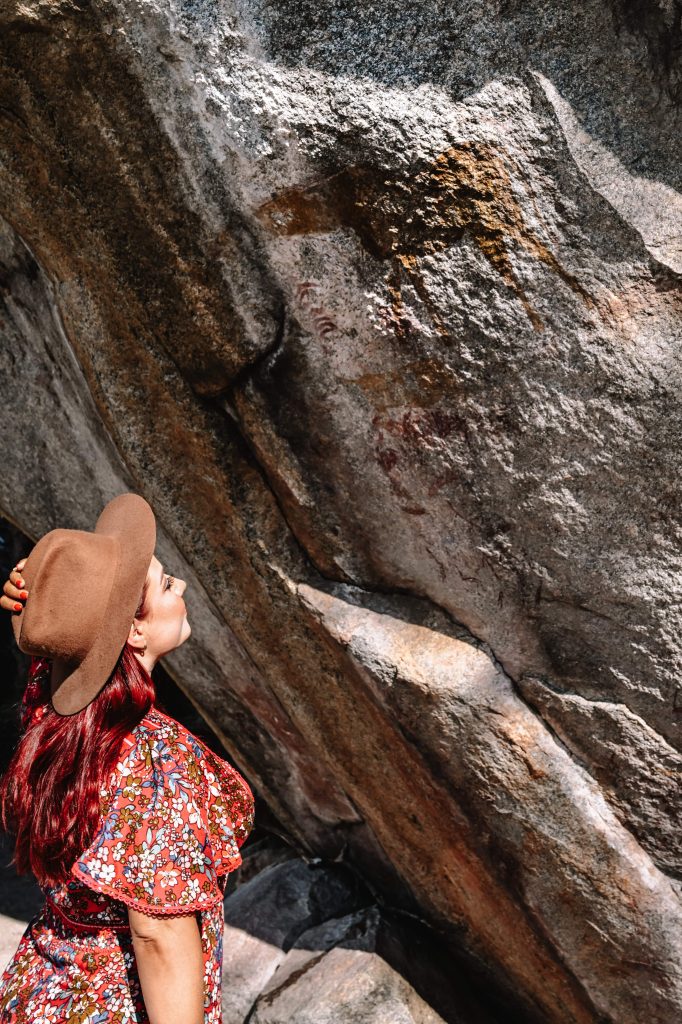

Matobo is Zimbabwe’s oldest national park; it is famous for the Matobo Hills, a range of balancing rock formations, the grave of Cecil John Rhodes, and its Stone Age rock art.

Matobo National Park boasts several thousand rock art sites like this painted by the Bushmen. “We estimate the oldest paintings at this site to be 16 000 years-old,” our guide said.

As anyone who has spent much time in southern Africa will tell you, there’s a quietness about places like these. The bush stretches on seemingly forever, and in a spare moment, you find yourself standing next to art painted thousands of years ago by someone who stood in the exact same spot, someone who felt the same cool afternoon breeze or the same heat of the sun.

There’s a weightiness and an importance to the feeling that cannot be replicated anywhere else. It may not be as flashy as spotting your first wild elephant in the bush, but it’s a moment just as irreplaceable. In moments like this, you feel the connection between the earth and yourself.

Moments like these are the ones worth coming here for.

The Bushmen, nomadic hunter gatherers, believed in sustainability and community with nature. They used absolutely everything they could from their hunts, but since the gallbladders of animals are inedible, they used its stomach acid in their paint. This is what has made their paintings so long-lasting, including this one of a hunter, a giraffe, and an antelope. Instead of being paintings, they are now acid etchings. These are lasting relics of an incredible people.

As our guide told us, “There are now only forty-five Bushmen surviving in all of Zimbabwe.” Approximately only 5 000 Bushmen are left anywhere in the world, most mainly living in the Kalahari. “They’ve been pushed to the furthest edges of where humans live,” our guide said. The Bushmen are also found on the farthest reaches of Hwange National Park where Zimbabwe borders Botswana.

“They were a wonderful bunch of people who believed in equality above everything,” our guide explained. They believed in mutual respect between themselves and nature.

Part of that legacy exists in Matobo National Park today, not just in the rock art paintings, but in the Park’s relationship to the local community.

As we headed in our game vehicle to explore more of the park, we stopped to smell khaki seeds, fragrant with granadilla and pineapple, and to watch a bushbuck disappear into a line of trees. Duiker with large, black eyes searched for bits of green among fields of dry grass, scorched earth, and prickly camelthorn trees. Whatever streams we passed were milky green and slow moving, and dry yellow grass darkened in the sun. Much of the park had been burned, as poachers burn 50 per cent each year in an attempt to distract rangers.

Now, new growth sprouted black soil, dotted with the bright skirts of women carrying bundles of thatch on their heads.

During winter, men and women from the local villages each cut forty to fifty bundles of thatch a day, making forty to fifty dollars. In a country with a high unemployment rate, this source of income is huge. For every ten bundles of thatch they collect, they give two bundles back to the park. It’s one of the ways the park works with the community rather than against it.

When witnessing this relationship the Park has to the community, it’s impossible to not remember the Bushmen who believed in the importance of community.

During our last hours in Matobo National Park, the high afternoon sun cast slanting light through tall yellow grass, as we walked from the local souvenir market, where brilliantly painted tapestries swayed in the breeze, further into the bush. “Do you want to see a rhino?” our guide asked moments before.

Of course, the answer is always yes.

Any chance to see a rhino in the wild is a precious one, as the chances of seeing a wild rhino become less and less every year. Fifteen years ago, there were one-hundred-and-sixty rhinos in Matobo National Park. Today, there are only sixty.

Female rangers led us through the yellow grass up to our waists; they scanned the landscape with intelligent eyes, eyes that see far more in the bush that I ever could. When meeting rangers who spend the majority of their time in parks like this, you can always sense not only their courage but their community with the land.

“Stop here,” one of the rangers said, and just through the tall, yellow grass, I could make out the rounded ears of a three-month-old rhino calf. The ranger mimicked the call of a rhino, perhaps letting the mother know we were there, she was safe. The mother rhino watched us intently, before laying down, eyes closed, to nurse her calf. I watched in stillness and awe, overcome by the gentleness and trust between the rhinos and rangers in this moment.

In this powerful moment, I couldn’t help but think of the Bushmen and the same trust nature must have had with them. These are the moments worth coming here for.

Megan Gilbert traveled with the Rovos Rail from Pretoria, South Africa to Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe. She is a travel writer, photographer, and a full-time traveler. Since she married in January 2023, she and her husband have visited eleven countries together. They can usually be found in Southeast Asia or driving around southern Africa in their 4×4. You can follow their adventure @meganthetravelingwriter and read more of Megan’s writing at meganthetravelingwriter.com